-

Title

-

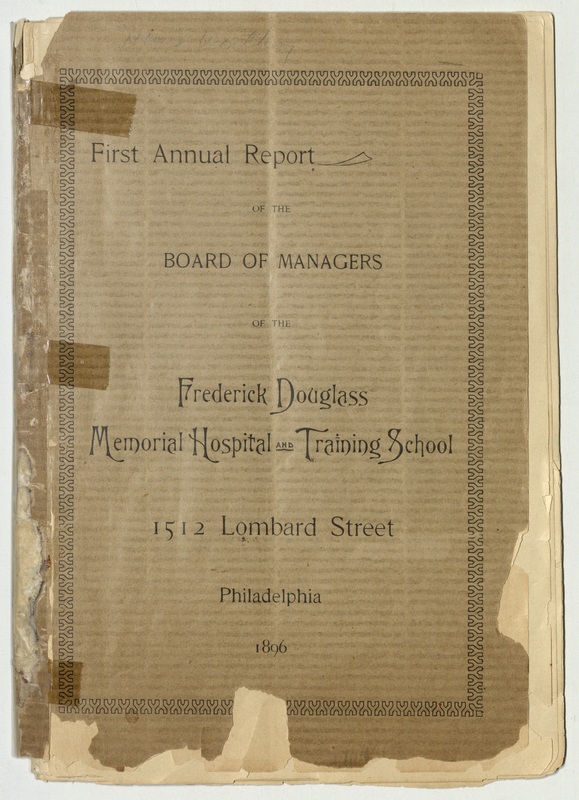

First Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School, 1512 Lombard Street Philadelphia 1896

-

Description

-

Founded in 1895 by Dr. Nathan F. Mossell (1856 - 1946), the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School was the first Black owned and operated healthcare institution in the country (Barbara Bates 1992).

-

Long denied equitable access to health care, the hospital served the black community of Philadelphia and provided professional opportunities to Black physicians and taught, educated and graduated Black nurses. Dr. Mossell, the first Black physician to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania, served as its chief-of-staff and medical director until his retirement in 1933. During Mossell's tenure, the hospital expanded its capacity and staff at the original location on Lombard Street. In 1948, it merged with Mercy Hospital to form Mercy-Douglass Hospital in west Philadelphia and remained open until 1973 (U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d.). Both hospitals had been created in direct response to the reality that Black patients were routinely turned away from white hospitals, and that Black nurses and physicians were excluded from training programs across the city.

The Report offers a rare and invaluable window into the daily operations and long-term impact of this institution. Comprising dozens of entries—marked with reference codes such as "MC.78.01" through "MC.78.50"—the report reads like a mosaic of administrative insight, hospital census data, in-patient & outpatient departments' (at its height it housed up to 100 beds) accounting facts, financials, clinical progress, and community service via its various clinics. More than mere numbers, it reveals how the institution was deeply embedded in the neighborhood it served—reaching beyond its walls through public health outreach, partnerships with civic organizations, and the ongoing education of Black medical professionals.

At its core, the hospital’s greatest legacy may lie in its nursing program, The Training School for Nurses (pp 30 - 35), which graduated dozens of Black women yearly. Many nurses entered the workforce as registered professionals at a time when their presence was still a political act. Their curriculum—comprising anatomy, obstetrics, surgical nursing, and public health—was as rigorous as any. In its early days, Hettie S.T. Williams, a renowned nurse educator, mentored generations of students while advocating for professional licensure and standards.

After Dr. Mossell retired, Dr. Wilbur Strickland was Board appointed as medical director. Several more individuals also stand out in the report shaping the hospital’s nursing mission. Dr. Strickland understood that to provide high quality and safe patient care, retain competent nurses, and train students per higher standards of nursing, the hospital needed to retain nursing staff, hire more nurse supervisors, graduate nurses and improve working conditions (Anchrum 2021). However he resigned in 1939, in protest because of patient safety concerns which stemmed from insufficient funding and was replaced by Dr. Russell Minton. Minton reorganized nurse scheduling and distribution to ensure adequate patient coverage and hired seventeen nurses’ aides to help ease the burden on nursing staff. In addition, all employees were put under employment contracts and prepayment hospital insurance. The hospital was long recognized for providing excellent nurse education and clinical experience, however despite these reforms retention was still a problem. In later years, Black nurses were able to find better pay and benefits elsewhere. Despite this, Ms. Louise Brashears, the second acting nursing director, submitted an urgent report on the “acute shortage of personnel in the hospital and a great need for replacements, as well as additional graduate staff nurses” (Anchrum 2021).

In spite of chronic underfunding the hospital endured—powered by community donations---Max Barber a civic leader and board member linked the hospital to Philadelphia’s Black press and philanthropic community, church support and strategic fundraising. Organizations like the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses and local women’s clubs stood beside it, offering volunteer labor, advocacy, and connection. In every sense, it was a lifeline—clinical, economic, and symbolic—to a community striving not just to survive, but to thrive. The nurse organization, established in 1908 realized early on that separate, parallel nursing status was never equal and sought to integrate its members into the wider nursing profession (Baker 1951). By the end of the 1920s, despite 71% of patients unable to pay for hospital services, talks of a merger began with Mercy Hospital. Unfortunately, the Great Depression disrupted this success, and like Douglass Hospital, Mercy plunged into financial trouble from which it never fully recovered (Schauffler 2020). Mercy-Douglass Hospital shuttered in 1973.

-

Rights

-

This work is believed to be in the Public Domain under the laws of the United States. For more information, see http://rightsstatements.org/page/NoC-US/1.0/

-

Creator

-

Mercy Douglass Hospital

-

Date

-

1896

-

Format

-

Booklet

-

Language

-

eng

-

Spatial Coverage

-

Philadelphia, PA

-

Publisher

-

Mercy Douglass Hospital

-

Contributor

-

Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing

-

Extent

-

50 pages

-

Identifier

-

MC.78

-

Date Created

-

1896

-

Subject

-

Segregation in education

-

Discrimination in medical care

-

Race discrimination--Health aspects

-

Hospital care

-

Nursing schools

-

Hospitals

-

Black, Doctor

-

Marginality, Social

-

Women in community organization

-

Fund raising

-

Patient advocacy