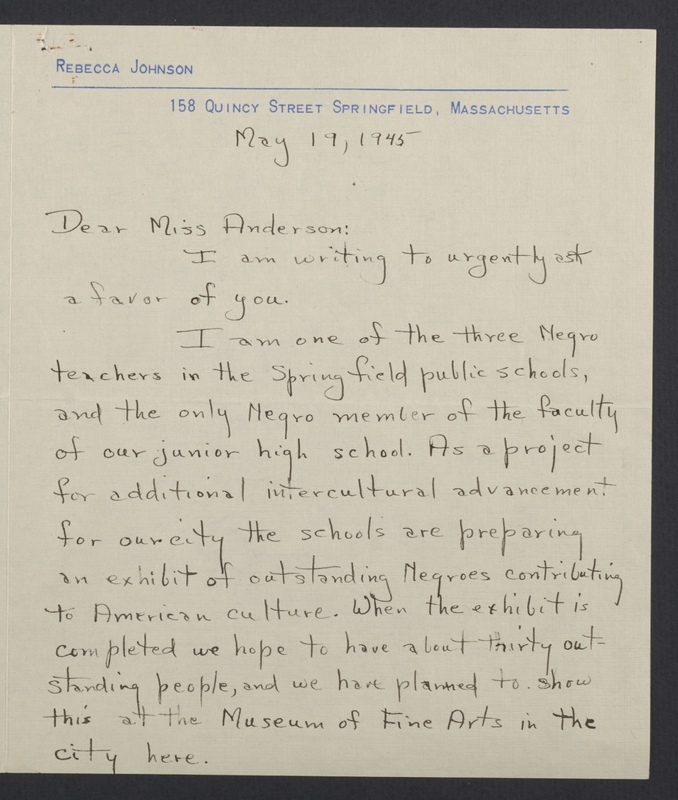

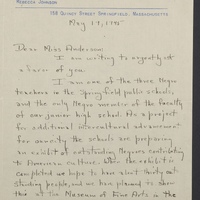

Letter, Rebecca Johnson to Miss Anderson, May 19, 1945

Item

-

Title

-

Letter, Rebecca Johnson to Miss Anderson, May 19, 1945

-

Rights

-

Copyright restrictions may exist. For most library holdings, the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania do not hold copyright. It is the responsibility of the requester to seek permission from the holder of the copyright to reproduce material from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts.

-

Date

-

May 19, 1945

-

Description

-

This letter was sent by Miss Rebecca Mary Johnson (July 10, 1905-October 4, 1991) to Miss Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897-April 8, 1993) on May 19, 1945. This letter was sent to share details about “a project for… intercultural advancement” that will feature famous Black Americans, like Marian Anderson (p. 1). Johnson asks Anderson questions about herself to be used in the exhibit for the benefit of the Springfield, Massachusetts community and youth.

-

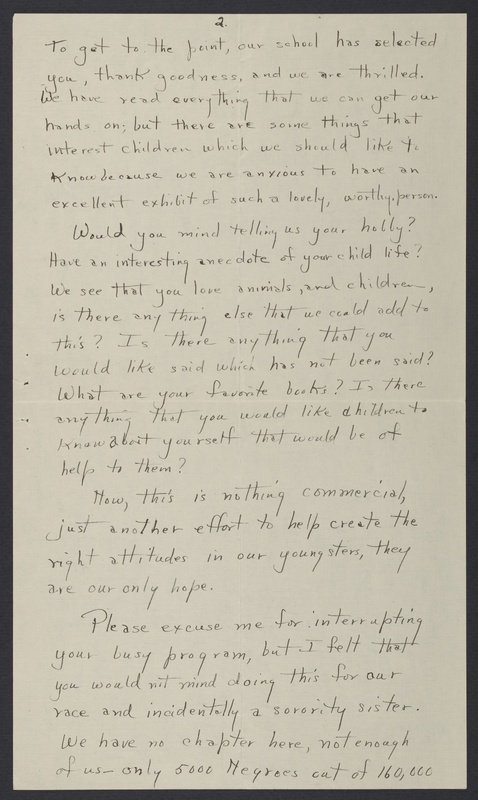

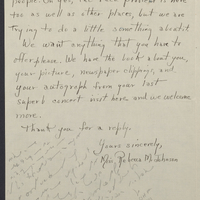

At the time that the letter was written, Johnson shared that she was “one of three Negro teachers at the Springfield public schools, and the only Negro member of the faculty of [the] junior high school” (p. 1). She indicated that “the race problem is here too… but we are trying to do a little something about it” by promoting awareness and knowledge about “outstanding Negroes contributing to American culture” (pp. 1, 4). Sharing Black history was a decades-long passion of Johnson’s (Shoemaker 1979; Union-News 1991). A newspaper article from 1979 covers her leading a Black History Week discussion to, in her own words: “learn about famous black people,” “to celebrate famous black people’s birthdays,” and “to say thank you for black people’s contributions to us, to America and to American life” (Shoemaker 1979).

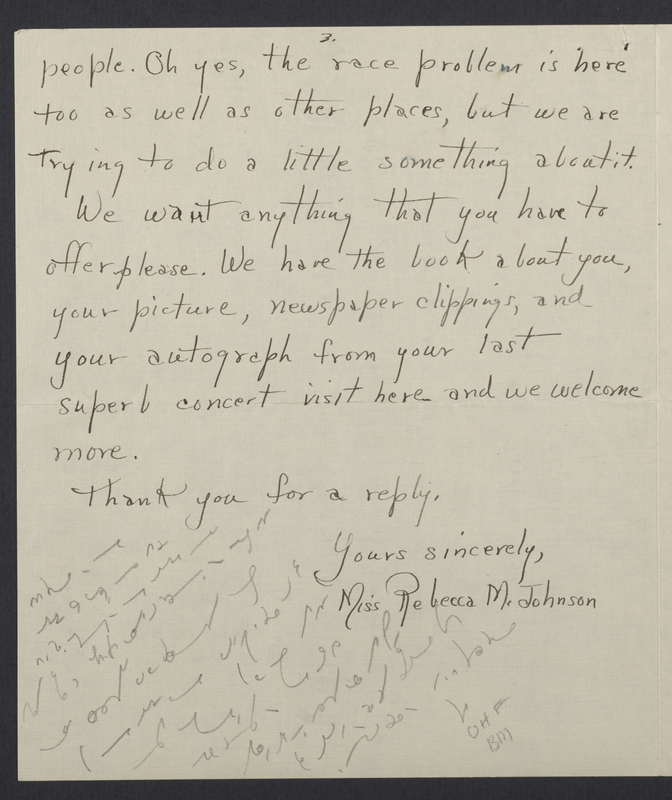

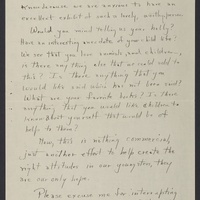

She asks Anderson a number of questions: her favorite hobby, a childhood anecdote, favorite books, learned wisdom for the youth, and for anything additional she would like to add (p. 2). She assumes Anderson “would not mind doing this for our race and incidentally a sorority sister,” presumably Alpha Kappa Alpha (p. 2). Finally, she requests for anything additional that she would like to share. She states that she already has her book, picture, newspaper clippings, and autograph (p. 3).

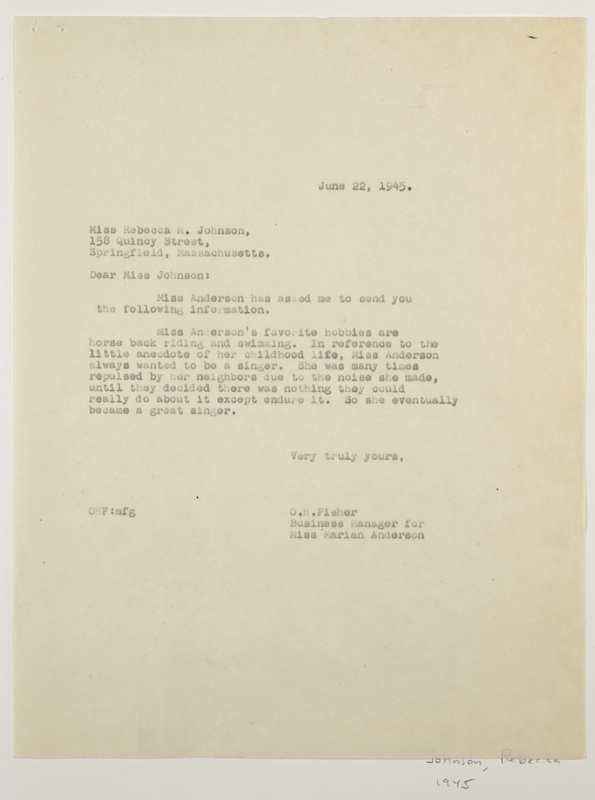

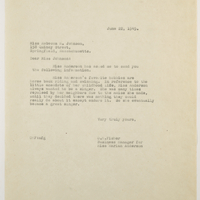

Anderson’s Business Manager Orpheus “King” Hodge Fisher (1900-1986) responded on June 22, 1945, per the request of Anderson. He was also an architect and eventually her husband, married on July 24, 1943 (Tatman 2025; Penn Libraries, n.d.). His reply indicated that Anderson’s “favorite hobbies are horse back riding and swimming,” and he shares a “little anecdote of her childhood life” in that she “always wanted to be a singer” (p. 4). She would always be singing and making noise, and her neighbors eventually “decided there was nothing they could really do about it except endure it” (p. 4).

Born to William Dorsey Johnson and Harriett Bell Goodwin, Johnson lived most of her life in Springfield, Massachusetts with the exception of higher education studies (Union-News 1991). At the time of writing this letter, she resided at 158 Quincy Street in Springfield, MA. She received her undergraduate degree from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, her Master’s from Columbia University Teachers College, and completed additional graduate work at Springfield College and Northwestern University (Union-News 1991). Highly regarded across the community for her “civic-mindedness” (Union News 1991) and being a “woman of firsts,” Johnson had most impact upon the youth wherein she “touched the lives of thousands of Springfield children” and held lasting relationships with each student regardless of race (Phaneuf 1991). The managing editor of the newspaper in which her obituary was written Wayne Phanuef (1991) was in school while Johnson was principal, and he wrote of her impact: “She helped a whole generation of white students ignore color. She was our leader. She had earned our respect and love.” She was the first Black junior high teacher and principal, and a Springfield school was named in her honor in 1990 to honor her over 48 years in public schools (Union-News 1991; Phanuef 1991).

Marian Anderson was born and raised in South Philadelphia to John and Anna Anderson, and had two younger sisters (Penn Libraries, n.d.). She would grow up to reach international fame as a contralto classical singer, and symbol of success and resilience (Penn Libraries, n.d.). Her singing career began in her family’s church chorus, and she sang and studied music and performance at William Penn High School and South Philadelphia High School for Girls (Penn Libraries, n.d.). Her church, local organizations, and the greater Black community helped to financially support and advance her early educational journey (Penn Libraries, n.d.). These opportunities and connections propelled her to local and regional fame; having first performed at the Philadelphia Academy of Music in 1918 and with the New York Philharmonic in 1924 (Penn Libraries, n.d.). She studied the arts internationally, making her first trip to Europe in 1928 (Penn Libraries, n.d.). At first funded by foundations and scholarships who saw immense talent in her, Anderson would continue to tour and travel internationally through her career (Marian Anderson Museum, n.d.).

Anderson is appreciated for paving the way for future Black performers, as she was the first Black female to perform at Carnegie Hall in 1928, the first Black singer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera in 1955, and the first Black singer to perform at a Presidential Inauguration in 1957 (Marian Anderson Museum, n.d.). She experienced racism in the United States more than other countries, and gently protested this in ways such as insisting auditorium seating be integrated, and “refus[ing] to sing where the audience was segregated” (National Marian Anderson Museum, n.d.). In 1936, Anderson performed at the White House in Washington, D.C. In 1939, she was to perform again in D.C.– her manager Sol Hurok suggested that she perform at Constitution Hall, the capital’s largest concert hall seating up to 3,702 people (Daughters of the American Revolution, n.d.). It is operated by the Daughters of the American Revolution, and they denied her the opportunity to perform due to the color of her skin (Penn Libraries, n.d.; DAR Public Relations, n.d.). Instead, she performed on Easter for over 75,000 people (plus radio listeners) on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial (National Marian Anderson Museum, n.d.).

Anderson received a plethora of awards, appointments, and over fifty honorary degrees including: an honorary membership in Alpha Kappa Alpha; honorary degrees from Howard University, Temple University, Smith College, and more; NAACP Spingarn Medal in 1939; the Philadelphia Award established by Edward Bok of which was particularly meaningful to her in 1941; appointment to the National Council on the Arts in 1966; the United Nations Peace Prize in 1972; Congressional Medal by President Carter in 1978; as well as the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991 (Penn Libraries, n.d.; Anderson 1955, pp. 273-275; Marian Anderson Museum, n.d.).

More information is available in the letter's image annotations.

-

Penn Libraries Digital Collection on Marian Anderson

-

Map to Miss Rebecca Johnson's address in Springfield, MA

-

Format

-

Text

-

Language

-

eng

-

Place

-

Springfield, Massachusetts

-

Contributor

-

University of Pennsylvania: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts

-

Extent

-

4 pages

-

Identifier

-

Box 124 Folder 7359

-

Subject

-

Anderson, Marian, 1897-1993.

-

Contraltos-- United States-- Biography.

-

Fan mail-- United States

-

Correspondence

-

Springfield, Massachusetts.

-

Black history heroes

-

transcription

-

REBECCA JOHNSON

158 QUINCY STREET SPRINGFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS

May 19, 1945

Dear Miss Anderson:

I am writing to urgently ask

a favor of you.

I am one of the three Negro

teachers in the Springfield public schools,

and the only Negro member of the faculty

of our junior high school. As a project

for additional intercultural advancement

for our city the schools are preparing

an exhibit of outstanding Negroes contributing

to American culture. When the exhibit is

completed we hope to have about thirty out-

standing people, and we have planned to show

this at the Museum of Fine Arts in the

city here.